Free French Paras…

- Posted on 06 Jul 2025

- 20 min read

By Hermes Editor Prosper Keating

With the Ilford 84 and London branches of the Parachute Regimental Association sending sizeable delegations to Paris at the end of this coming September to parade with the French Union Nationale des Parachutistes for Saint Michael’s Day, it seems appropriate to recall the historical links between British and French airborne forces through this common Free French history.]

As many readers know, the French regular army paratroopers’ beret is a brighter red than the British maroon beret but some French parachute regiments wear maroon berets like ours, pulled over to the left in the French style. This tradition recalls the Free French origins of these units, formed and trained in Britain as part of the patriotic rebel General Charles de Gaulle’s army-in-exile.

The French paratroopers of the 1er Régiment de Parachutistes d’Infanterie de la Marine (1 RPIMa) on the left wear maroon berets with the French version of the British Special Air Service badge of which the Who Dares Wins motto is rendered in French: Qui Ose Gagne.

Like the 2ème and 3ème Régiments de Chasseurs Parachutistes, who also wear maroon berets, the 1 RPIMa inherited the traditions of the wartime Free French parachute units attached to the British Army’s Special Air Service as 3rd and 4th SAS.

As any self-respecting British paratrooper knows, the maroon beret was not adopted until July 29th 1942 and was not worn in action by The Parachute Regiment until November that year, during fighting in North Africa. Seeing the distinctive headgear, the German Fallschirmjäger of the Ramcke Brigade nicknamed the British paratroopers “red devils”. The German paratroopers were known by the Allies as the Grüne Teufel or green devils and one of their musicians had even written a marching song entitled Grüne Teufel. The maroon beret was generally described in the past as the red beret and those who wore it as red devils.

The Free French Paras posted to North Africa as the French Squadron of the Special Air Service, which would become 4 SAS, were issued with the SAS sand-coloured beret, which they retained after their return to England following the conclusion of the North African campaign to distinguish them from other Free French paratroopers as desert veterans. The British sub-units of the SAS had by then received the maroon beret worn by the rest of British Airborne Forces.

The Free French parachute units were all granted the right to wear the maroon beret by King George VI in 1944 and every Free French paratrooper parading in Paris on Armistice Day on November 11th 1944 wore the maroon beret in the French style. The FFL SAS men wore their SAS beret badges and SAS wings. Other FFL paras wore a modified Parachute Regiment badge as introduced in 1942 but shorn of the dog and basket, as some British paras irreverently called the Imperial lion and crown.

Men who had taken part in three combat operations could wear their British wings over their left pockets rather than on their right shoulders. By 1942, the FFL had their own parachute wings, designed by Georges Bergé, with a shield bearing the Cross of Lorraine on a shield superimposed on the parachute. These wings were worn over the right hand breast pocket.

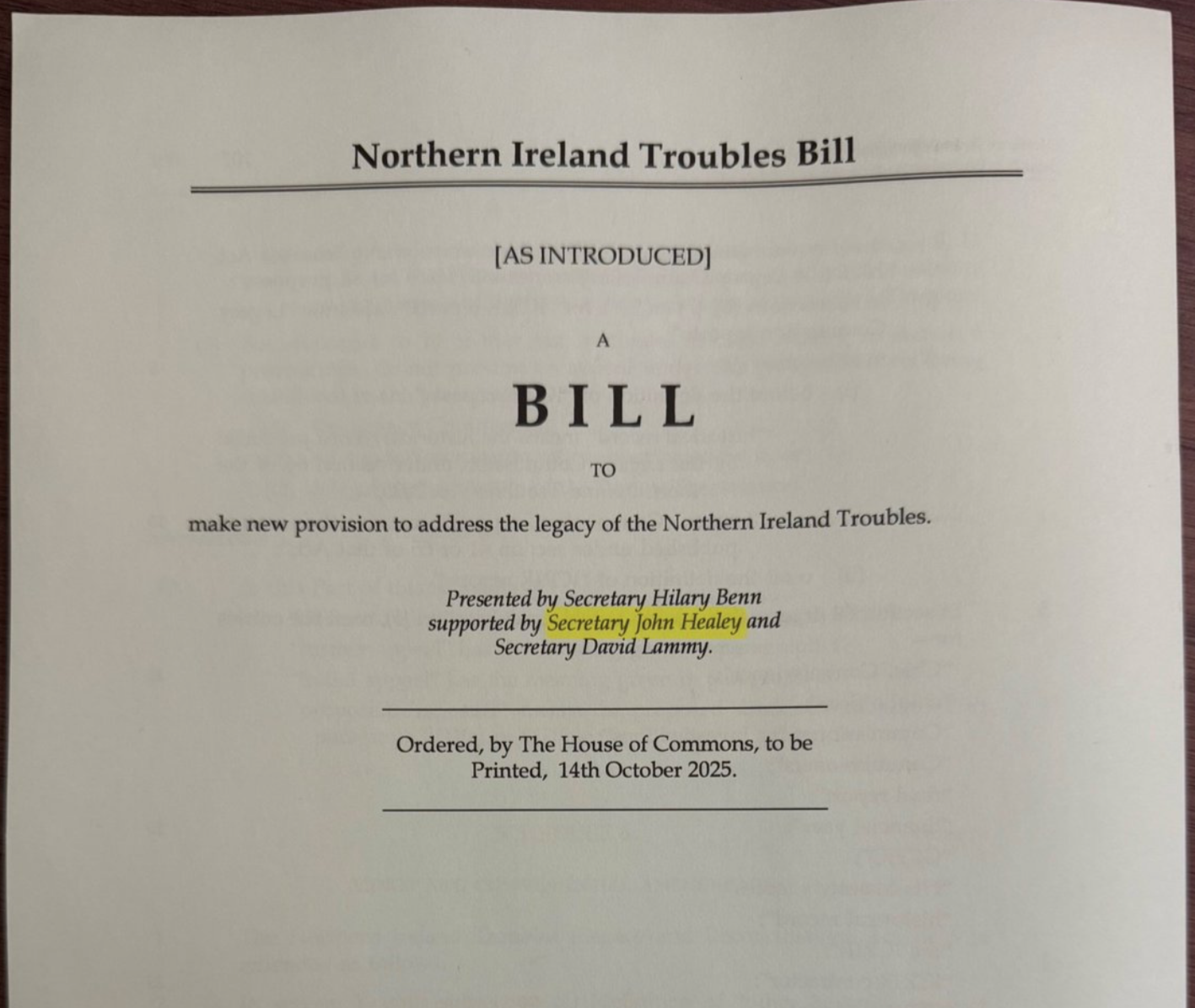

Britain had sent military observers to the Soviet Union and to Germany in the mid and the late 1930s where they saw the new Red Army and Wehrmacht parachute units mounting mass parachute jumps during their annual military exercises. However, it was not until after the startling success of the German parachute and glider assaults during the invasions of the Low Countries and Norway in April and May 1940 that Prime Minister Churchill suggested to the War Office the formation of a 5,000-strong parachute corps.

Amongst the French soldiers, sailors and airmen gathering in the vast Olympia exhibition hall in London’s Earl’s Court in June and July 1940 after the Dunkirk evacuation in June were a few men who had served with the 601e Groupe d’Infanterie de l’Air. Olympia had been chosen because it had its own railway station as well as a London Underground station on a short spur of the District Line. It was also well-served by buses and was convenient for the Great West Road and other highways in and out of London.

Formed on April 1st 1937 in the eastern French town of Reims, the 601 GIA was France’s first parachute unit, its first officers and instructors trained in the Soviet Union. A second company-sized unit, the 602 GIA, would be formed in French Algeria at Baraki, just outside Algiers, on October 1st that year.

These two units were part of the French Army Air Force. Like many good French units, they were not committed to battle in the War of 1939-1940, during which the French armed forces still managed to make the Wehrmacht pay dearly for its victory. The French high command had sent the 601 GIA to join the 602 at Baraki in March 1940 at the height of The Phoney War. The 601 and 602 GIA were disbanded on August 25th 1940 under the terms of the Franco-German armistice of June. The French Vichy government would later form a couple of small parachute units but this article is not concerned with them.

One of the French Army officers who found his way to London in that summer of 1940 was Captain Georges Bergé, who had sustained several bullet wounds on May 18th 1940 in northern France. Convalescing in his parent’s home in Mimizan on the French Atlantic coast between Bordeaux and Biarritz, Bergé was scandalised when he heard Marshal Pétain announcing the planned Franco-German armistice by radio on June 17th 1940.

Born in January 1909, Bergé was a career infantry officer who had earned his parachutist brevet with the 601 GIA in 1937. Health issues prevented him from jumping with the unit and he returned to the infantry in 1938. In September 1939, Bergé was serving with the 13th Infantry Regiment, a grand old regiment that traced its roots back to the 16th century, when he was wounded.

After Pétain’s broadcast, Georges Bergé heard Charles de Gaulle’s famous call-to-arms of June 18th 1940, broadcast by the BBC in response to Marshal Pétain’s announcement. The Royal Air Force also dropped printed copies of de Gaulle’s speech over France during the coming days. As the framed example from the author’s collection shows, these leaflets were required to carry an English language version, which can be seen on the bottom left hand side of the document.

Bergé left his parents’ home and headed south towards Spain. In Saint-Jean-de-Luz, a fishing port a dozen kilometres north of the frontier, on June 21st 1940, he boarded one of the boats heading for England carrying volunteers for General de Gaulle’s army-in-exile. Three days later in London on June 24th 1940, Georges Bergé succeeded in getting in to see de Gaulle and proposing the formation of a parachute infantry unit as part of the rebel General’s army-in-exile.

General de Gaulle was interested in Bergé’s idea but did not act upon the Captain’s suggestion right away. Instead, he appointed Bergé second-in-command of the Free French Forces depot at Olympia. On August 1st, de Gaulle told Bergé to write a proposal of no more than one page. Having read it, the General marked Bergé’s proposal as approved and added his signature.

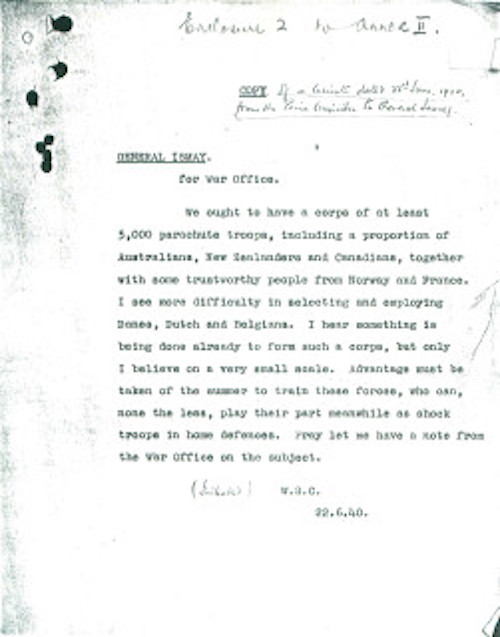

Two days before Bergé’s first interview with de Gaulle, Winston Churchill had written to Lieutenant General Hastings ‘Pug’ Ismay at the War Office on June 22nd 1940, suggesting the formation of a 5,000 man-strong parachute corps comprising volunteers from the British Army and Empire forces. In his letter to Ismay, Churchill suggesting including “some trustworthy people from Norway and France.”.

As soon as de Gaulle’s signed approval came through, Bergé and his Senior NCOs began looking for likely recruits amongst the Free French volunteers. The parachute training was assured but the men first underwent British Army commando training as their de facto selection process for the planned parachute infantry company. Like the prewar 601ème Groupe d’Infanterie de l’Air, the new Free French parachute unit would come under Air Force command.

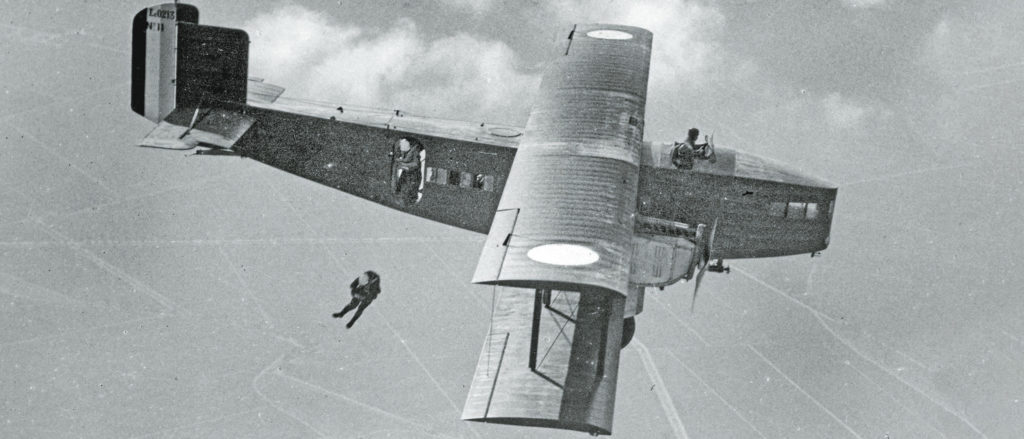

On September 29th 1940, Free French HQ issued General Order N° 765 authorising the formation of the 1ère Compagnie d’Infanterie de l’Air (1 CIA) of the Forces Françaises Libres, naming Bergé as Commanding Officer. Early in December 1940, the 1st Section travelled with their CO Bergé to the Central Landing Establishment RAF’s parachute training school at RAF Ringway near Manchester, opened on June 21st 1940. This establishment would later become N° 1 Parachute Training School or 1 PTS.

When they returned just before Christmas, the Frenchmen all wore on the right shoulders of their British Army-issue Battle Dress the new Parachute Badge with Wings designed the previous September. The new qualification badge was formally approved on December 28th by Army CounciI Instruction (ACI) 1589/40 — Badges for Parachute Troops. Georges Bergé had also earned the British Army badge.

As well as their British Battle Dress and equipment, these early Free French paratroopers wore the French-style side hat made in England of British Army khaki serge before being issued with black berets like those of British Army tank crews but worn in the French style, pulled over to the left. In addition to the British Parachute Wings, they wore British-made versions of the French brevet parachutiste introduced in 1937. Georges Bergé had not yet designed the special Free French parachute wings.

To be continued…