BLOODY SUNDAY – A PARATROOPER REMEMBERS…

- Posted on 06 Nov 2025

- 21 min read

By Anonymous

Certain events and moments in time must be always be mentioned – history will always dictate that it would be wrong to gloss over them. Especially when those on the ground that day fervently argue that the real story significantly differs from the narrative recounted by terrorist propagandists, repeated by mainstream media and propagated by successive governments with vested interests.

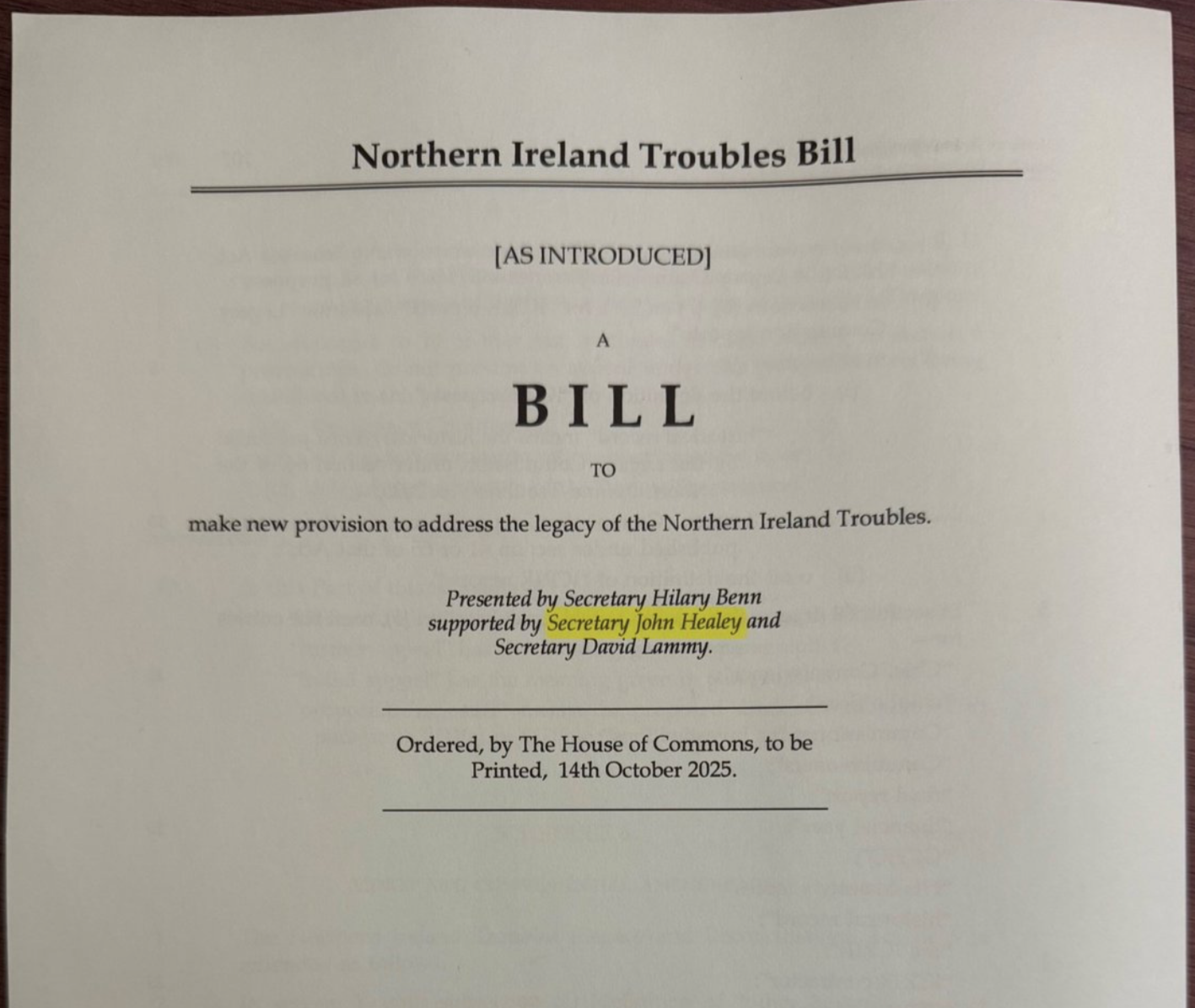

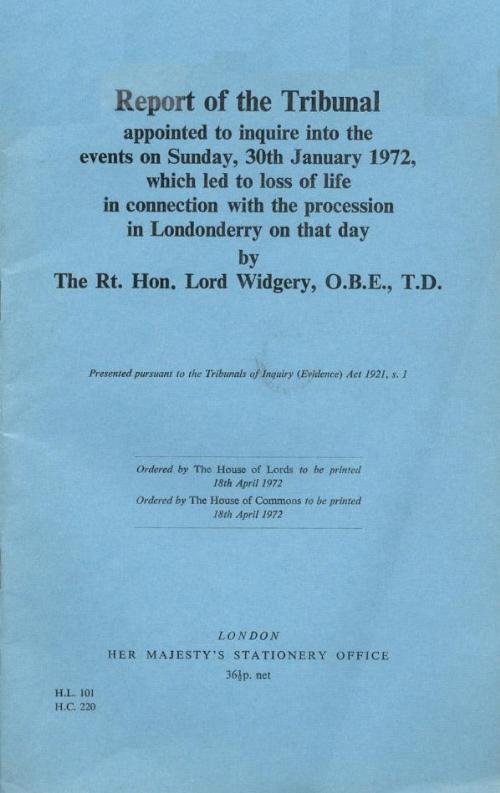

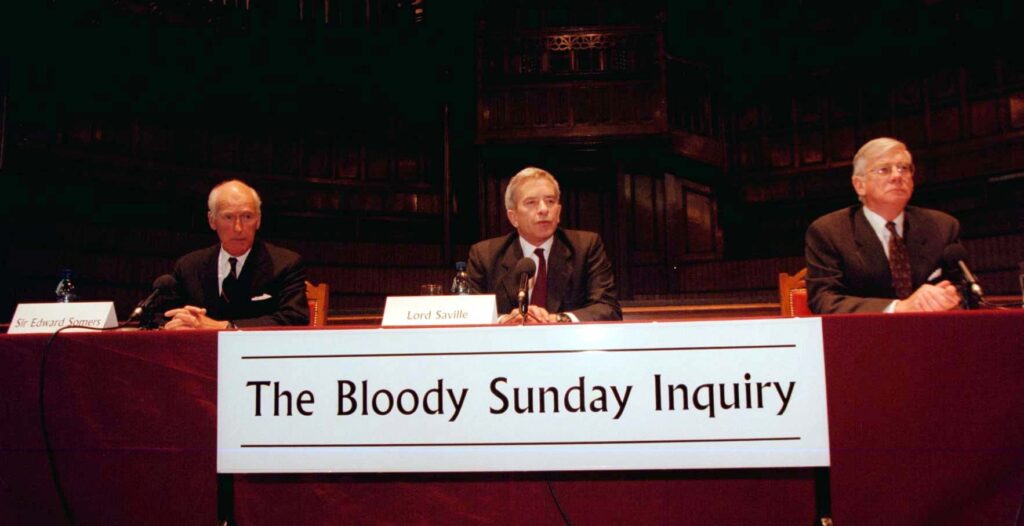

Much has been written over the years about ‘Bloody Sunday’, and several inquiries have come and gone. Rarely have these been about what really occurred. The Widgery Tribunal, which was convened soon after the event, completely exonerated soldiers of 1st Battalion, The Parachute Regiment (1 PARA). In contrast and nearly three decades later, Lord Saville’s 5,000-page report, delivered in 2010, found that soldiers’ actions were unjustified, and that none of the thirteen victims had posed a threat.

It is a strange situation when you consider that every soldier in the British Army must be able to identify and hit a target at a range of 300 metres, and yet, despite the alleged indiscriminate shooting into a packed crowd of several hundred, the death toll was so limited. And that the victims were all just innocent bystander, who, as it so happens, just found themselves in the middle of a riot.

It is also worth noting, with the exception of Soldier F, who was [recently] found ‘not guilty’ of murder and attempted murder some fifty-two years after the event, that no one [else] has ever been charged. [Add hyperlink to George Simm article] As Rupert Murdoch would say, never let the truth get in the way of a good story.

Why 1 PARA was deployed to Londonderry has remained, to all intent and purposes, opaque, as most of the paratroopers on the ground found themselves on the cordon ‘babysitting’ other military units that should have been more than capable of protecting themselves. Leaving one to reasonably construe that the intelligence picture had indicated the presence of a very real threat.

Certainly, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) controlled the Bogside and Creggan estates with an iron fist. Before the ‘Security Exercise’ commencing 30th January 1972, Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and Army patrols had been systematically pushed out of these locations, which became ‘No-Go’ areas.

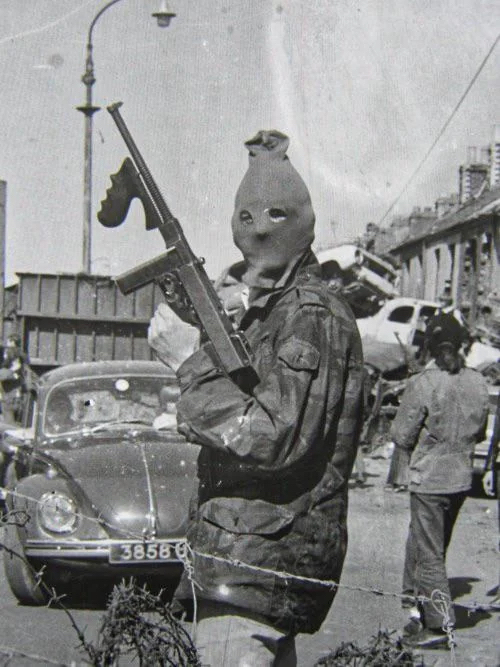

Photos of armed PIRA members patrolling inside the Bogside – mimicking Security Forces operations outside of the estate – circulated in the local news publication. The republicans’ description of the area as ‘Free Derry’ perpetuated the myth. PIRA would mount opportune attacks on the military from within the Bogside, who would then retaliate, and this would produce a ‘tic-for-tac’ effect of attack(s) and counter-attack(s).

In an all-out effort to curtail this senseless situation, the Security Forces gave ground and reduced their presence to a minimum, trying to maintain a low profile. Many saw this as giving way to PIRA and its supporters, even though it was well-intentioned and designed to reduce tension. For their part, PIRA viewed it as a victory.

By September, there existed an uneasy ceasefire. Somehow, the UK Government of the day had thought this would isolate PIRA elements; however, as a result of a well-coordinated PIRA-Sinn Féin propaganda campaign, the republican terrorists only got stronger. PIRA were able to persuade acquiescent elements within the local population to rebuild over forty barricades in key positions around the city, producing choke points and making it once again even harder for Security Forces to mount patrols. Even mobile patrols were seriously hampered.

Thus, the Londonderry PIRA were able to defend crucial locations with just a few gunmen – a tactic that was underestimated at that time – with the intention of showing other republican areas around the province that they were a force to be reckoned with. Using Londonderry as a showpiece, PIRA hoped to escalate their campaign and reproduce similar situations elsewhere. If this were successful, it had the potential to cause an all-out civil war in Northern Ireland.

Sniping and bomb attacks became more frequent, and the RUC could not or would not enter certain areas, being content to adopt a containment strategy. The Bligh’s Lane factory, manned by No. 8 Infantry Brigade, was like a Wild West fort surrounded by Red Indians and was just as ineffective. It was 8th Inf Bde’s job to secure the local area, and they attempted this with every means at their disposal.

Battalion-strength ‘Search and Arrest’ operations were the order of the day, but instead of dominating the ground, they just served to turn the remaining locals against the Army. Nail and petrol bomb attacks on static RUC and Army positions doubled overnight. Crowds of youths gathered to draw Security Forces ‘Snatch Squads’ out into the open.

The crowd would then part down the middle, and a gunman who had been using them as cover would open fire on the soldiers or policemen. The Security Forces were unable to return fire for fear of hitting ‘innocent’ unarmed civilians who had closed ranks to conceal the gunman and cover his escape. This was a tactic used time and time again with a great deal of success. In other instances, PIRA used women and young children, who were as good as bulletproof shields.

In some locations, PIRA erected their own searchlights to illuminate Security Forces and hinder their movements at night. Locals took turns staying up all night to act as an early warning system against patrols. The banging of dustbin lids against a wall or the use of whistles would alert gunmen should Security Forces approach. Shops in Waterloo Place and Great James Street were set on fire and Williams Street became the unofficial dividing line between PIRA and the Security Forces.

From August 1st 1971 to February 9th 1972, in the Londonderry alone, no less than 2,656 shots were fired at the Army and the Police. 456 assorted nail and hand-thrown bombs exploded. 255 charges were detonated in a variety of premises. In comparison, 840 shots were fired in return by police and Army personnel with very little effect.

For soldiers transformed into a ‘quarry’ permitted to return fire only when targets were positively identified, fighting an opponent who can blend into the civilian population was a no-win scenario. Two soldiers were killed and quite a few wounded at this time, and up to £6 million-worth — the equivalent of around £100 million today — of civilian property was damaged or destroyed by PIRA.

Sniper fire confined units to secure positions and made patrolling Williams Street impossible during daylight hours. It was only possible to operate during the hours of darkness. Gangs of republican youths roamed the area, trying to bait and lure Army patrols into the sights of the snipers. The rule of law became non-existent.

To compound matters further, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) decided to hold a march and rally against the UK Government’s internment policy even though it would be illegal. The peaceful intentions of the march may well have been genuine, although misguided. Despite PIRA’s promises of no violence to the NICRA, it was too good an opportunity for PIRA to miss with so many soldiers and policemen guarding the routes and providing numerous static targets.

The Army Commander intended to contain the marchers by erecting corrugated iron barriers across the more sensitive streets to control the direction of the march. By doing this, he hoped to keep any damage to a minimum. In theory, it was a good idea. Other smaller barriers made of wooden cross beams, topped with barbed wire were to be used by smaller individual units. Placed in front of temporary secure locations, the objective was to discourage any rioters from charging head-on and overwhelming positions. This type of temporary defence hadn’t changed for centuries but remained fit for purpose.

1 PARA was in reserve, having been transported up from Belfast the day before and tasked as ‘Snatch and Arrest’ squads if the crowd got out of hand and the situation turned ugly. The main containment would be carried out by 8 Infantry Brigade with the 1st Battalion of the King’s Own Border Regiment and two companies of the 3rd Battalion Royal Regiment of Fusiliers. There were two water cannons as additional backup.

The marchers assembled in the Creggan Estate on the sunny Sunday afternoon of January 30th 1972. The mood was good-natured. It took a while for the crowd to build up, but eventually, the numbers swelled to around five thousand people. The usual rabble-rousing republican politicians, including the Independent Republican MP Bernadette Devlin, were castigating the government and agitating the crowd from a truck in front of the demonstrators.

It seems ironic that Bernadette Devlin’s life was saved by 3 PARA medic a few years later , in 1981, after Protestant extremists burst into her home and tried to shoot her dead in front of her husband and children. Devlin was hit nine times and owed her life to that paratrooper medic who tended to her before a British military helicopter evacuated her to hospital. Was she grateful? Not even a thank you. [Devlin claimed that 3 PARA were there to ensure that the assassins got into her home and then escaped afterwards. In reality, the 3 PARA patrol captured the would-be killers — Ed]

The marchers moved off, and at this stage, there was still no trouble. It was a complete cross-section of the community marching that day, including women and children. As they approached Williams Street and the barriers, some stones were thrown, mostly by a small group of yobs who had detached themselves from the main march. The Security Forces did not retaliate.

To their credit, the crowd marshals turned the main crowd away from the barriers. It was obvious that they didn’t want a confrontation with the Army. More yobs detached from the main group and started pelting the Williams Street position with missiles. The Royal Green Jackets, who were manning this location, took a few minor casualties. They attempted to drive the hooligan group back by firing rubber bullets but the youths used an improvised shield ripped from one of the corrugated iron barricades to protect themselves from the volley.

A water cannon was brought up and sprayed the rioters with purple dye, but before it could make much of a difference to the worsening situation, someone in the crowd threw a CS gas canister under the vehicle and the crew, who had stupidly forgotten to bring their respirators with them, were forced to reverse away from the area. The riot was contained for the moment, but the decision was then made to send in elements of 1 PARA as ‘snatch squads.’

To be continued…